BOOK PROJECT

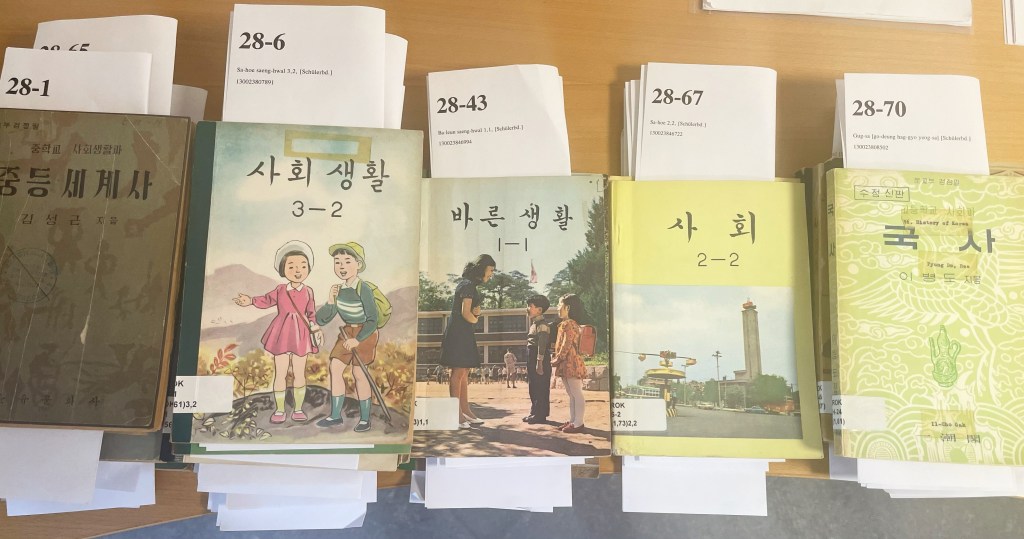

Photo: South Korean textbooks. (These textbooks were obtained via interlibrary loan from the Georg Eckert Institute in Germany and sent to my office in Copenhagen in 2022 for digitization.)

Democracy at School: Authoritarian Education, Post-Transition Citizens, and the Long Shadow of the Cold War in South Korea and Poland (with Steven Denney)

To what extent does the Cold War continue to shape contemporary politics, and what are its lasting legacies? This study examines the long-term effects of Cold War politics through a systematic analysis of secondary school textbooks produced during the era’s authoritarian regimes, as well as surveys from post-transition countries. Focusing on two contrasting cases (South Korea’s US-backed anti-communist regime and Poland’s Soviet-supported communist regime), it offers the first comprehensive review of the full corpus of secondary-level history and social studies textbooks in both contexts. All materials have been digitized and are being pre-processed for machine learning to identify underlying narratives and patterns.

This research follows a two-step design. The first phase adopts an inductive approach, analyzing a large corpus of textbooks to identify similarities and differences between communist and anti-communist messages and to develop a novel theory of propaganda and legitimation under both regimes. We pay particular attention to regimes’ state-building visions, which are incorporated into their regime legitimation messages. While messages from communist regimes have been widely studied, those from anti-communist regimes have received less attention, as they tend to lack ideological coherence and often rely on the imposition of external threats for legitimization. Nevertheless, the legitimizing messages of anti-communist regimes continue to influence citizens in certain parts of the world, including South Korea. Rather than assuming that anti-communist regime messages were less organized than their communist counterparts, this study seeks to compare how these regimes responded to communist messaging through counter-messaging strategies.

The second phase tests this theory using survey instruments to examine the long-term effects of these messages on the political attitudes of post-transition citizens. We expect that divergent visions of authoritarian state-building and legitimation create different expectations about the role of the state. We argue that these expectations do not easily change after a transition to democracy. First, expectations about the role of government serve as a subtle form of authoritarian messaging, meaning that citizens may internalize these messages without critically evaluating them or connecting them to the authoritarian regime. Second, such expectations help foster a civic culture that can be transmitted across generations, shaping citizens’ political behavior, including how they identify the most important policy areas and/or evaluate policies.

In our survey, we test whether the legitimation messages recovered in phase one continue to resonate with post-transition citizens experimentally to ensure the causal link. For each authoritarian-era message, we construct a democratic-era analogue expressing the same policy domain or value dimension but grounded in democratic norms. Respondents evaluate the appropriateness or desirability of each statement for contemporary society. This approach allows us to directly observe whether citizens find authoritarian-era messages normatively acceptable, persuasive, or reflective of their own expectations about governance. Because both the authoritarian and democratic statements are matched in length, domain, and linguistic tone, differences in evaluation can be attributed to the underlying political logic rather than surface characteristics. The design is fully randomized, enabling comparisons across (1) within-cohort effects, (2) post-transition cohorts, and (3) intergenerational transmission.